Prime Minister Keir Starmer was all smiles at Jaguar Land Rover HQ on 8 May, hailing a “landmark” trade deal with the United States, details of which emerged following a meeting with President Donald Trump’s team at the G7 summit on 17 June.

Contrary to expectations, the UK-US Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD) offered no immediate tariff relief for the steel, aluminium, or pharmaceutical sectors, leaving those negotiations for a later date.

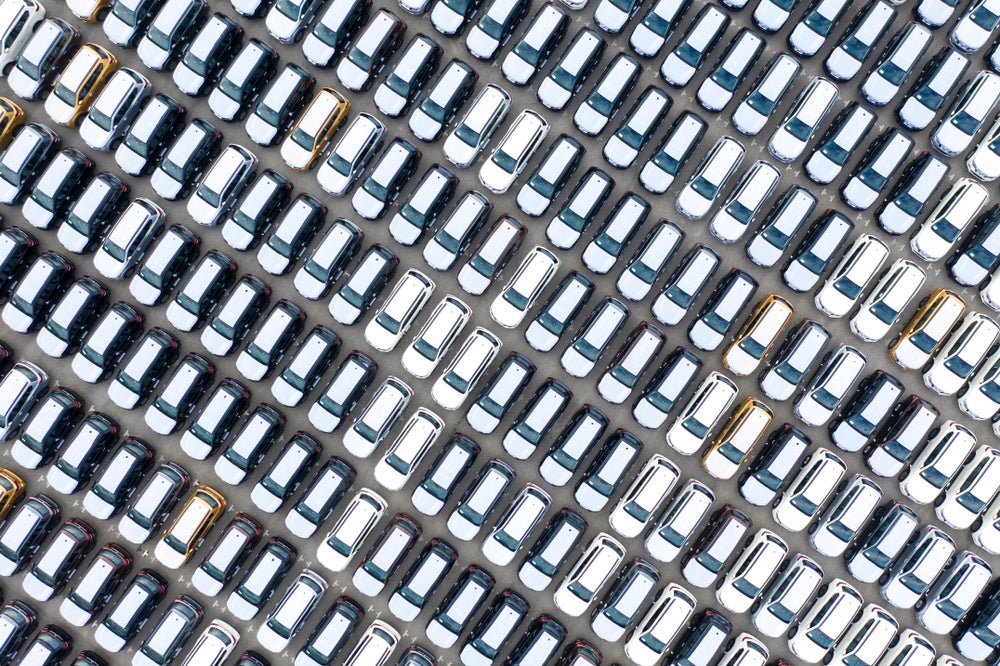

Most headlines, however, framed the deal as a strategic triumph for Britain’s flagship exporters in automotive and aerospace. For British carmakers, the EPD delivered an initial three-year US tariff reprieve, saving millions and “safeguarding thousands of automotive jobs,” as Whitehall proudly declared. Export quotas are roughly in line with current UK shipments to the US, leaving little room for growth. Still, with the US representing a huge market for premium brands, the win is particularly favourable for high-value luxury and performance vehicle exporters.

The big winners are Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), Aston Martin, Bentley, Rolls-Royce, Mini, McLaren, and Lotus, iconic UK brands with low volumes but high value. Yet, all are foreign-owned, meaning while some reinvestment may occur, the bulk of profits is likely to be repatriated abroad.

Collateral damage in the tariff war

One essential British industry has paid a heavy price: bioethanol.

This isn’t just about one plant in Hull. Vivergo Fuels, the UK’s largest producer, will shut by year-end, ending domestic ethanol and animal feed production and cutting 160 skilled jobs. Ensus, the last major player, faces a market flooded with duty-free US ethanol and is now in urgent talks with government to avoid collapse.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWith the UK’s 19% import tariff gone and a US quota large enough to cover the entire UK market, Britain has effectively ceded its ethanol future to the US Midwest. For the Renewable Fuels Association in Washington, the deal is a gift: guaranteed access to one of the fastest-growing export markets, with UK demand set to rise under E10 and potentially E15. For the UK’s Renewable Energy Association, it is a disaster: a domestic industry sidelined just as demand for its product should have been increasing.

More than just motoring fuel

Ethanol is not an optional extra in the UK’s energy mix; it underpins E10 petrol at every forecourt. As the Department for Transport moves toward E15, reliance on imports will only grow.

But bioethanol’s significance extends far beyond the pump:

- Agriculture: Supplies high-protein animal feed, reducing reliance on imported soy.

- Food & Drink: Fermentation by-products provide captured CO₂, essential for meat processing, beverage carbonation, and packaging.

- Healthcare: Captured CO₂ supports medical gases critical for surgeries and pharmaceuticals.

Ensus alone produces 250,000 tonnes of captured CO₂ annually, a capability that will vanish if production shuts down. In effect, this is not just a blow to transport fuels, but to the UK’s wider industrial base.

Winners and losers

Vehicle exports dwarf bioethanol’s £332.6m revenue and 6,000 supported jobs. Aerospace also secured a clear win: 10% tariffs on aircraft engines and components were eliminated, benefiting giants like Rolls-Royce, Airbus UK, and BAE Systems. This sector employs over 100,000 people and contributes a £14.7bn trade surplus, cementing its status as a cornerstone of UK manufacturing.

Yet even here, the picture is not flawless. Much of aerospace’s export growth depends on goods sold for military and dual-use purposes. If Britain can profitably export to nations accused of human rights violations and war crimes, why cannot it not sustain homegrown industries like bioethanol, a sector vital for food security, agricultural resilience, and the clean energy transition?

Irony

The EPD exposes a striking irony: while the US fiercely protects its domestic ethanol industry, Britain has effectively handed its own sector to American producers with no reciprocal safeguards. British bioethanol, once a pillar of transport fuel, agriculture, and industrial CO₂ supply, is now left exposed to the volatility of global commodity markets and currency fluctuations. The deal may have secured short-term wins for luxury cars and aerospace, but it has left a vital domestic industry vulnerable, a reminder that trade triumphs on paper do not always translate to strategic security at home.